differential diagnosis

Non-syndromic periodontal diseases

It is essential to distinguish between non-syndromic periodontitis coincidently occuring in a patient with a Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and periodontal manifestations as part of the syndrome “periodontal EDS“.

Periodontal diseases span from mild, reversible gingivitis to irreversible loss of periodontal attachment resulting in loss of teeth. “(Plaque induced) gingivitis” on the one hand is outlined by bleeding on probing as only the gums are inflamed due to bacterial biofilms. “Periodontitis” on the other hand shows gingival inflammation as well as destruction of the periodontal tissues, consisting of gingiva, cementum, periodontal ligament and alveolar bone. Parodontal attachment loss can be diagnosed radiological or by periodontal probing. In addition to these clinical features receding gums so called “gingival recessions” can occur, which are exposures of the tooth roots. This is not a specific sign for periodontitis but can also occur due to a thin gingival biotype and over exaggerated tooth brushing. In this case the recessions are located only buccal or lingual. Gingival recessions as a result of periodontitis are also located interdentally (11).

The struggle in clinical differentiation between the periodontal features of EDS and other conditions such as chronic periodontitis or aggressive periodontitis lead to easy confusion. “Chronic periodontitis” prevalence ranges from 10 to 83 % depending on age and severity (18). With a mean prevalence of 11.2 % severe periodontitis is the sixth- most prevalent condition in the world (19). The exemplary chronic periodontitis patient is over 30 years of age, with the amount of bone destruction consistent to the presence of plaque and calculus (20). The disease is characterized by slow progress but bursts of destruction. Furthermore the progression can also vary with local factors, systemic diseases and extrinsic factors for example smoking or emotional stress (11).

Due to this high prevalence of chronic periodontitis in the general population, one patient may coincidently show an EDS phenotype and periodontal disease. This may falsely lead to the erroneous classification of periodontitis as a manifestation of EDS. Moreover, if systemic features are mild, pEDS may also be mistaken as aggressive periodontitis (21).

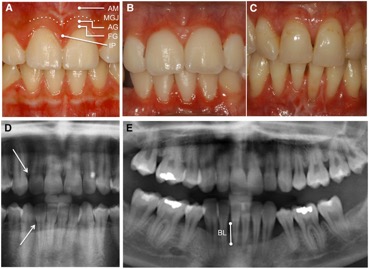

There are a number of specific oral aspects of periodontal EDS which might help to differentiat pEDS from chronic / aggressive periodontitis: Additional oral characteristics of pEDS are:

(1) Severe gingival inflammation in response to mild biofilm accumulation

(2) a striking lack of attached gingiva causing oral tissue fragility

(3) periodontal breakdown without pocketing but severe gingival recession

(4) pattern of alveolar bone loss described as localized to any region, proceeding in a domino effect from one tooth to the next

(5) prominent vasculature on the palate

The difference to individuals suffering from chronic or aggressive periodontitis to those from pEDS is the thin and fragile oral soft tissue with missing attached gingiva in individuals suffering from pEDS (Figure). This clinical feature eases the clinical diagnosis before signs of periodontitis show. Because of the missing of the attached gingiva the thin and mobile alveolar mucosa continuous directly into the free gingival margin (terminal edge surrounding the tooth), this causes the fragile tissue. Normally this free gingival margin is connected to the attached gingiva which itself is connected to the periostum underneath by collagenous fibrils. This connection is responsible for the protection during chewing or tooth brushing (13).

Vascular EDS

Vascular EDS is the second main differential diagnosis to pEDS as the clinical presentation of the patient is similar except for early and severe periodontitis. vEDS affected individuals show nonhyperelastic, thin and translucent skin, through which the venous pattern over chest, abdomen, and extremities is visible. Hypermobility of joints is minimal and limited to small joints such as fingers and/or toes, nevertheless a dislocation of the shoulder can occur. Acrogeria as another clinical appearance is shown in extremely thin, wrinkled skin covering the hands and feet, what makes the patients look “older”. In contradiction to this the facial skin appears tight, not unlike after a facial-lifting procedure. The facial characteristics are a thin, delicate and pinched nose, thin lips, hollow cheeks, prominent and staring eyes, firm and tight pinnae of the ears and frequently missing of a free ear lobule (22-24).

Inguinal hernia and congenital club foot are frequent, as well as keratoconus, and venous varicosity and thrombophlebitis. Yet the hallmarks of vEDS are the cruel, life-threatening internal complications, usually occurring after puberty and which include spontaneous ruptures of arteries, the colon, and gravid uterus, as well as (hemato-) pneumothorax (25). Yet there does not appear to be a specific type of complication for familial predisposition as different catastrophic events can occur within one large family or even in one person (26,27).

Constipation is an important factor in the pathogenesis if colonic perforation, where as rupture of the colon, most frequent in the sigmoid region, is the most common problem. It occurs at sites where the bowel surface seems normal (28).

Complications in late pregnancy, or even during/after delivery include vascular, intestinal, or uterine ruptures, vaginal lacerations, prolapse of uterus and bladder, as well as premature delivery as a result of cervical insufficiency or fragile membranes (29-36). These pregnancy related complications led to death in 9 – 15% of pregnant women (37).

Pulmonary complications may be the result either from primary defect in the lung parenchyma or from primary intrathoracic vascular rupture (38).

Periodontal manifestations in vascular EDS: Individuals with vascular EDS may show generalized thinness and translucency of the gingiva and the mucosa (48), but there is no evidence that periodontitis is a clinical manifestation of vascular EDS.

Classical EDS

The classical EDS (cEDS) clinical hallmark is vascular fragility, which will lead to spontaneous rupture of medium sized arteries as an additional sign to other EDS signs. This is a rare but important differential diagnosis to vascular EDS (11). Other clinical features are separated into major and minor criteria for diagnosis. Major criteria are skin hyperextensibility and atrophic scarring as well as generalized joint hypermobility. Minor criteria include easy bruising, soft skin, skin fragility, molluscoid pseudo tumors, subcutaneous spheroids, hernia, epicanthal folds (4).

For this subtype there are two different mutations that are grouped in the same clinical entity “classical EDS”. They were put together because they only differ in their degree of involvement and are periodically allelic. They cover about 90% of all the cases of EDS (5). The more common mutation is a heterozygous mutation in one of the genes encoding type V collagen (COL5A1 and COL5A2). This is the cause in more than 90% of cEDS patients (39-41). The rather rare mutation affects genes encoding type I collagen (COL1A1) (42).

Periodontal manifestations in classical EDS: Periodontal manifestations in classical EDS are rarely described. Some cases of classical EDS may possess a predisposition to localized periodontal breakdown related to single teeth with dentinal dysplasia (46).

Hypermobile EDS

The hypermobile EDS (hEDS) typical manifestations are quite severe, generalized joint laxity and as a result to this problems such as dislocations, effusions, and precocious arthritis. The most common affected joints are the shoulder, patella, and temporomandibular joints. Skin hyperextensibility is variable because tissue fragility is absent, this is can be used to differentiate from pEDS, vEDS and cEDS. Atrophic scars, spheroids, or molluscoid pseudotumors with joint hypermobility are common features in hEDS as well as cEDS (5).

For this EDS subtype there is no reliable or appreciable genetic analysis yet, so the diagnosis remains clinical. Referring to gender and age the syndromes may be presented differently. Furthermore joint hypermobility ranges from asymptomatic joint hypermobility through “non-syndromic” hypermobility with secondary manifestations to hEDS. Therefore the clinical diagnosis consists of 3 main criteria (4):

Criterion 1: Generalized joint hypermobility (GJH)

The Beighton score (see diagnosis) is the most accepted tool for assessing GJH at present. A score of 5 out of 9 points has to be achieved for the incorporation into the Villefranche nosology. Yet joint motion and range decreases with age (Soucie et al., 2011; McKay et al., 2016), so the cut-off of ≥5 points may result in an over-diagnosis in children and an under-diagnosis in adults and elders. As a result to this some minor adaptions should be considered for the diagnosis of hEDS, because GJH is defined as a prerequisite for the diagnosis of hEDS and is heavily effected by acquired and inherited conditions such as sex, age, past-traumas, co-morbidities, etc.) A new proposal made by the Committee on behalf of the International Consortium on the Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes suggests ≥6 for pre-pubertal children and adolescents, ≥5 for pubertal men and women up to the age of 50 years, and ≥4 for those >50 years of age for hEDS. This varies from other subtypes of EDS but these types have confirmatory testing (4).

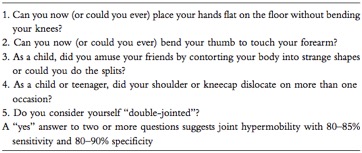

For individuals enduring joint limitations, such as past surgery, wheelchair, amputations, etc.,affecting the Beighton score a five-point questionnaire regarding historical information may be included (43,44). If the Beighton score is one point lower considering the age and sex specific cut-off with the questionnaire being “positive”, that means ≥2 positive questions, the diagnosis of GJH can be made (4).

Criterion 2: Two or more among the following features A – C must be present

(For example: A and B; A and C; B and C; A and B and C)

Feature A: Systemic manifestations of a more generalized connective tissue disorder (five have to be met)

- Unusually soft or velvety skin

- Mild skin hyperextensibility

- Unexplained striae (such as striae distensae or rubrae at the back, groins, thighs, breasts and/or abdomen in adolescents, men or prepubertal women without history of significant gain or loss of body fat or weight)

- Bilateral piezogenic papules of the heel

- Recurrent or multiple abdominal hernia (umbilical, inguinal, crural)

- Atrophic scarring involving at least two sites and without the formation of truly papyraceous and/or hemosideric scars as seen in classical EDS

- Pelvic floor, rectal and/or uterine prolapse in children, men or nulliparous women without a history of morbid obesity or other known predisposing medical condition

- Dental crowding and high or narrow palate

- Arachnodactyly, defined as: (i) positive wrist sign (Steinberg sign) on both sides; (ii) positive thumb sign (Walker sign) on both sides. One or both have to be met

- Arm span-to-height ≥1.05

- Mitral valve prolapse mild or greater based on strict echocardiographic criteria

- Aortic root dilatation with Z-score ≥ +2

Feature B: positive family history, with one or more first degree relatives independently meeting the diagnostic criteria for hEDS.

Feature C: Musculoskeletal complications (one has to be met)

- Musculoskeletal pain recurring daily for at least 3 monts in two or more limbs

- Chronic, widespread pain for ≥3 months

- Recurrent joint dislocations or frank joint instability with no trauma: (i) Three or more atraumatic dislocations in the same joint or two or more atraumatic dislocations in two different joints occurring at different times (ii) Medical confirmation of joint instability at two or more sites not related to trauma. One has to be met

Criterion 3: All the following have to be met

- Absence of unusual skin fragility, as a prompt consideration of other types of EDS

- Exclusion of other heritable or acquired connective tissue disorders, including rheumatologic conditions. With Patients suffering from an acquired connective tissue disorder, such as lupus, rheumatoid, arthritis, etc., both Feature A and B of Criterion 2 have to be met to additionally diagnose hEDS. Feature C of Criterion 2 cannot be counted towards a diagnosis of hEDS in this situation

- Exclusion of alternative diagnoses which may also include joint hypermobility, for example hypotonia and/or connective tissue laxity. These alternative diagnoses include neuromuscular disorders (e.g., myopathic EDS, Bethlem myopathy), other HCTD (e.g., other subtypes of EDS, Marfan syndrome), and skeletal dysplasias. Exclusion of these may be based on history, physical examination and/or molecular genetic testing.

Only when all of these three criteria are met simultaneously a diagnosis of hEDS should be assigned.

Other diagnostic criteria that are not specific for hEDS but may prompt consideration of hEDS in differential diagnosis are for example sleep disturbance, fatigue, postural orthostatic tachycardia, functional gastrointestinal disorders, dysautonomia, anxiety and depression (4).